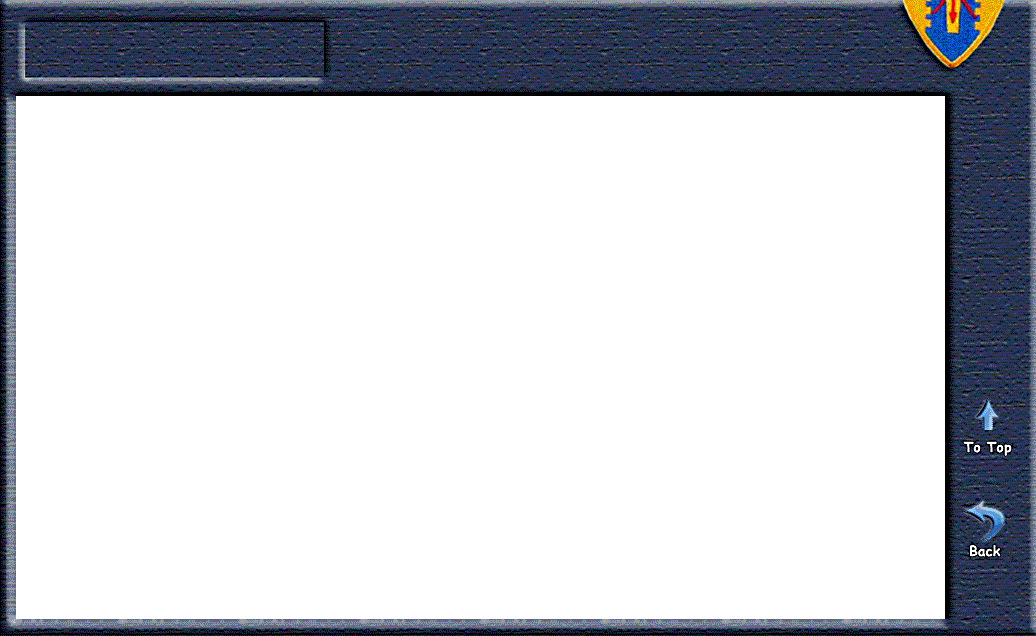

Wife Visits Her Centaur in Vietnam - 1966

by Ruth Ann Burns (Carl's wife)

(God called and she went to Heaven early Easter morning 9 April 2023. My son and I were with her during the final minutes… Carl)

"A wife visits her soldier husband in Vietnam; It Cost $2000 and Was Worth Every Cent"

Parade Magazine Article, 18 December 1966, by Ruth Ann Burns

Photos by James H. Pickerell

Saigon, South Vietnam

After what seemed like an eternity, I saw him standing behind an iron fence waiting for me. I ran to him.

I was wringing wet from the sudden change in temperature (70 degrees to 107 degrees) and covered with dust, left behind by an Army jet that had just taken off in a hurry.

"You look beautiful," he said.

Lt. Carl W. Burns, 24 of Summit, NJ, is a US Army helicopter pilot with a Purple Heart (he has been shot down three times), but at that moment he was just Carl Burns, husband, and he belonged to me, not the US Army. The war disappeared for a second into our magic world of togetherness. We were afraid someone would pinch us, and the dream would be over.

The eternity had lasted 29 flight hours, seven Pan American dinners, five stopovers, an ocean, countless letters to Congress, the Pentagon and the White House and months of plotting. And it was going to cost $2000.

"You will never be able to do it," I had been told when I first decided to travel 12,000 miles to the war zone. As a wife, I wanted to see my husband. As a reporter, I wanted to cover the war.

"You will never be able to do it," I had been told when I first decided to travel 12,000 miles to the war zone. As a wife, I wanted to see my husband. As a reporter, I wanted to cover the war.

Nobody thought it was more ridiculous than my family. "Why do you want to go? It's a crazy idea. You're only 21. You don't know how bad it is over there. Besides, you look 16. No one is going to take you seriously."

But 18-year-olds were dying in blazing jungles half a world away, my husband was flying a helicopter out of some place called Cu Chi, and the war was being dissected daily in discussions with my schoolmates at college. I felt an overwhelming need to know what it was doing to my husband. Married only six months when my husband left, I vowed secretly to be in Vietnam for our first anniversary.

When I first mentioned my idea to Carl before he left, he dismissed it. "Too dangerous," he said. But I got a job on the daily paper in New Brunswick, NJ, and the editor saw the dramatic potential of the story. I'd be the youngest accredited correspondent in Vietnam…a female in the war zone who just happened to have a helicopter pilot for a husband. Wait a minute!

"Every publisher worries when sending a reporter to a war assignment," the publisher of the paper said, vetoing the idea. "But in your case I couldn't sleep nights knowing I was responsible for putting your life in danger." The thought of a 5-foot, 100 pound blonde covering the war frightened him.

I did the only feminine thing to do. I went home and cried. But nothing was going to stop me.

Now the nights were filled with furious typing – to congressmen, senators, the Pentagon and, in desperation, to President Johnson. I was trying to hitchhike a ride in return for writing a series of articles for the Army. The responses were sympathetic – with regrets. No free rides. Luckily, however, I was able to get enough commitments from assorted publications to guarantee my expenses (round-trip fare: $1200) and my accreditation.

New York in Saigon

Carrying a typewriter and the top layer of our wedding cake, packed in dry ice, I left for Vietnam. Nobody quite believed my plane ticket – destination Saigon – and a soldier who sat next to me from Hawaii to Japan said, "Boy, I'm scared for you. I've been trained for six months for this war, and I'm not even ready to go."

The minute I stepped off the plane at Tan Son Nhut airport, Saigon, I knew this was the land I had read about. The searing heat jumped at me …the dust was in my face…armed soldiers surrounded me. Carl was nowhere in sight, but then we found each other, and suddenly we were on a bus to our hotel in Saigon. In the midst of a rush hour traffic jam that would do justice to New York City, the strange sights of war unfurled.

On the surface the people carried on as if there were no such thing as the Viet Cong. Except for the white cement drums protecting every potential assault position and the barbed-wire fences, it could have been any Far Eastern city, crowded and shabby.

Our hotel wasn't exactly the Saigon Hilton. There were no towels, no soap. The shower was a trickle of water, turning alternately hot and cold at its own whim. The dining room had not been recommended by Duncan Hines, but it was described in our guidebook as "the gathering place of the elite." The guidebook neglected to mention that the elite had four legs. Brown lizards slithered playfully along the ceilings and walls as we ate. "This isn't the most beautiful place in the world for a second honeymoon," my husband apologized.

"Being together makes it the most beautiful," I said, adjusting to the distant thunder of artillery.

During the next two days, a sticky problem of credentials was resolved, and there was enough time to visit the shops on Tu Do Street. Sometimes we rode the motorized rickshaws that are commonplace on the streets of Saigon, and Carl remembered that my father had been complaining about my fast driving back home. "I think I'd rather take my chances with you than with these Saigon drivers," he needled. Saigon drivers seem to have been trained at the same driving school as New York cabbies.

Sometimes we just walked, hand in hand. I was so excited about our reunion it was three days before I noticed the Vietnamese were staring at us. It seems any public display of affection between a man and a woman is considered bad form here. About the same time I noticed something even stranger – to me. On the streets, boys hold hands with boys, and girls hold hands with girls. It is perfectly proper.

We traveled to Army camps, orphanages, hospitals, schools, hamlets – and the war focused clearly for us, and our understanding grew. I asked Carl the question some people at home were asking: "Should we be here?" He had fought and lived here six months, had been shot down and had debated the question with other GI's.

"We belong here," he said. "There is no doubt about it in my mind. There may have been a better time and place to make this stand against Communist aggression, but it was not made. The fact is, our country made it now, and there is a job to be done."

How often I would hear this opinion expressed over and over in different words from privates, generals, and civilians.

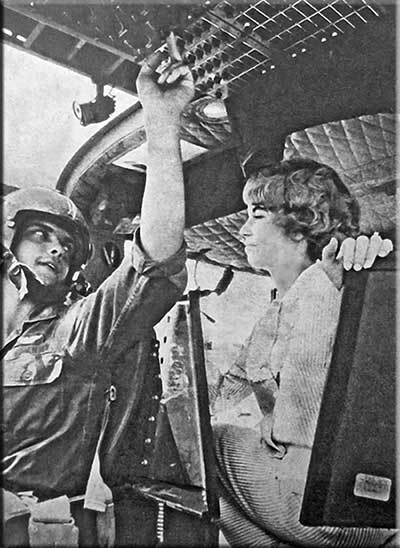

"More and more, the military is fighting a dual war," Carl explained. "You'll see the quiet war now."

Traveling slowly along a rutted dirt road, we came upon a village school deep in Viet Cong territory. Children stared curiously at our jeep – and at me. They had never seen an American woman before, and blonde hair was alien to them. Soon the sad-eyed waifs were surrounding the jeep and shouting, "No. 1…No 1." In Vietnamese slang, there is no higher praise. They saw Carl as some sort of king because he had the only light-haired woman in VC land – in a pink and white dress yet!

In the middle of the jungle a medical unit fought for the trust of the villages. Their weapons were not guns but medicine, soap and food. I can't forget the infected sores on hundreds of small children approaching an American doctor for help. "The people at home should see this," Carl said. "That is what you're thinking, isn't it?"

As I watched a Vietnamese peasant woman cook rice over a fire, I thought of life at home. Her home was a thatched-roof hut with two rooms. Her seven children slept on bamboo slats without sheets, but there was a bomb shelter for protection from Viet Cong attack.

"The villagers are in a bind here," Carl told me. "They are confused and afraid to take a stand. The Americans come, and they are naturally suspicious at first. They fear VC retaliation for friendliness to Americans. When nightfall comes, the country goes back to the VC. The enemy is never pushed out completely. The VC return and make the villagers answer for their deeds."

The war was becoming very real to me. The elusive enemy that returns to terrorize the pacified hamlet…the hurt look in the eyes of the orphaned children we visited … the strength of the Vietnamese trying to root out the VC…all of this would remain with me.

Progress is a creeping thing in this war. There are no big battles that capture a village, and there are no big gains on the ground. You don't gain 12 yards today and two miles tomorrow. A gain is seeing a mother smile when her child is cured by a Med Cap doctor. A gain is the look on a farmer's face when he is taught new methods of agriculture. A gain is the trust and the confidence of people being swayed away from the Communists' to the Americans' side. A gain for my husband's unit is a small villager of 9 who warns the daily convoy going into Saigon about three mines set by the VC overnight. His intelligence report saves American lives. Why does he do it? Because, he says, the Army doctor treated his sister and made her well.

The quiet war has its own victories.

Sharing every minute together, our understanding grew. We learned together.

At home newspaper accounts of the war seemed remote, the picture just beyond the point of focus. For Carl, participating as a pilot brought him closer to the total scene, but he had never really met the people. He had never even been to Saigon. My trip gave us both a chance to get to know the South Vietnamese and the war situation a little better.

Sightseeing in Saigon meant bargaining with the local salesmen for a fair price … holding our noses as we passed through the open market where freshly slaughtered meat hung … watching the ancient Buddhist rites at the nearest temple. Saigon was the knowing smile on the waiter's face as we entered the dining room each night. To another waiter he would whisper, "Same, same." (Translation: Married.) Everyone would watch as we were seated.

The days went quickly, and finally, on our first wedding anniversary, I had to leave, and Carl had to go back to Cu Chi. Waiting at the airport, Carl already was reliving memories.

"Remember how you jumped at first when you heard the artillery firing? And the way you looked in the helicopter flying over VC land?" It didn't work. Tears spilled down my face.

"Of all the anniversaries we will have in the future," he whispered, "this will be the best one because I got the most precious gift of all for two weeks – you."

The last one to get on the plane, I turned to glance back at the tiny Asian land that never again would be 12,000 miles away from me. For now, this was my war, too.