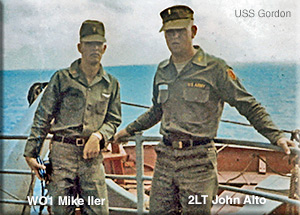

The Trip Aboard the USS Gordon - 1966

Carl Burns - also see story by Gary Hatfield

Well, if you think there would be little happening at sea during a two-week period, you were never aboard a troop transport ship.

Well, if you think there would be little happening at sea during a two-week period, you were never aboard a troop transport ship.

Our exact date of departure was kept secret until close to departure. We were told to be packed and ready. The two and a half ton trucks picked us up at Schofield Barracks for the ride to the docks. Officers, troopers, and Chopper were all set to go, ready or not here we come.

Chopper was our troop mascot and some of the troopers thought that if the First Cavalry Division could sneak a donkey aboard, they could sneak our mutt Chopper. Chopper was really Sergeant Roland Petty’s dog in Hawaii. He sniffed boots at morning formation and gained 25 pounds in Vietnam while most of us lost that same amount. If you recall Lady and the Tramp, Chopper was the tramp.

We mill around for what seemed hours; well, it was hours. It was just before dusk as I remember. We’re finally told to line up, don’t recall in what pecking order. We receive bunk assignments; I look at mine and say with joy, “Look at this; I’m in stateroom 11.” As in a countdown there were 14 "me too's.”

Upstairs

We make our way through the ship and find five rows of bunks, stacked three high. Being the first officer in I do a quick survey and pick a top bunk under an air vent. Being on top you don’t get anyone else stepping on your bunk. There was one small sink for all, two small portholes, but where is the head?

We make our way through the ship and find five rows of bunks, stacked three high. Being the first officer in I do a quick survey and pick a top bunk under an air vent. Being on top you don’t get anyone else stepping on your bunk. There was one small sink for all, two small portholes, but where is the head?

Major Bob Graham describes our journey to our “stateroom” as up and down stairs with a duffle bag, helmet bag, and a ditty bag being wider than the hallway. There also seemed to be no direct route to anywhere, upstairs to get downstairs, side to side, good luck. There was no privacy; your bunk was your kingdom. The food was good, with service by stewards in white uniforms. There was a small officers’ day room that was usually jammed.

Now remember, this is Pearl Harbor. We were going to sneak out of the harbor under the cover of darkness. Didn’t know the North Vietnamese Army had an air force.

Next morning most of us venture to watch what we can see on deck. This is no WWII convoy; this is just the Gordon and nothing else. It would be that way for most of two weeks.

Time, time, lots of time except for me. Seems the ship’s captain was looking for an editor of the ship newspaper. My good friend Captain Russ Catania gets wind of this and tells the ship’s captain, “Burns was editor of his high school newspaper.” Tag, I’m it, editor of The Gordonaire. My instructions for this four page mimeographed daily were, remember it’s for all troops, nothing about a specific religion, nothing unpatriotic, keep it clean, meaning no sex stories. Now, how do you produce a paper with those limitations? My editorial office was an eight foot by eight foot cage for the editor, two reporters, a wireless operator, and a printer (aka) mimeograph operator. So we printed good news from home, sports, more good news from home, and more sports, plus an article of local interest, meaning the Gordon. The ship’s chaplain had final say as to content.

Warrant Officer Bill Carroll reports on the discovery of a sun deck on the highest level of the ship. Guys began to explore the ship after three days out. For several days some warrant officers and junior grade officers would put on bathing suits under their fatigues, grab a paperback, and head up to the sun deck. There were chaise lounges in a storage closet. How good can it get, a juicy paperback and some great sunshine? Until a field grade officer heard of this and made the sun deck off limits to all except field grade officers.

Warrant Officer Bill Carroll reports on the discovery of a sun deck on the highest level of the ship. Guys began to explore the ship after three days out. For several days some warrant officers and junior grade officers would put on bathing suits under their fatigues, grab a paperback, and head up to the sun deck. There were chaise lounges in a storage closet. How good can it get, a juicy paperback and some great sunshine? Until a field grade officer heard of this and made the sun deck off limits to all except field grade officers.

Of course there was griping and then a revelation that NO field grade officers were taking advantage of their privilege. Mysteriously a poster was hung in the officer’s mess announcing a dance on the sun deck for field grade officers only. The decision was reversed. I don’t remember if this made The Gordonaire or not. It probably was censored as being too hot for an issue.

For most of the officers daily life remained the same, sleep, eat, watch one of possibly two movies, write home, read books, nap, play cards, go up on deck to see the same thing as yesterday with the hope that the waves were higher or we see another ship on the horizon.

And the absolute most ceremonial non-event was writing letters to home. I begin a letter to my wife on March 20, 1966. “Dear Ruth Ann, sorry I didn’t write yesterday but it would have been quite different as yesterday wasn’t really yesterday. We crossed the international dateline yesterday but we are not skipping a day until tomorrow. Seems that the chaplain’s commander-in- chief has a lot of pull and Sunday services were not going to be skipped. So we were inducted into The King Neptune Society or something like that a day late.”

On March 27, 1966, we pull into Okinawa. All hands on deck to see something. The 1,000 or so marines that shared the cruise with us disembarked. I did not hear of much trouble between the marines and the 25th Infantry Division soldiers. We were not allowed off.

We depart after about six hours headed for Vung Tau in Vietnam. Not much adventure but we did get to see land. We anchor off shore for a few days. The military police with regularity throw concussion grenades overboard to thwart any grenade launches from VC divers. Rumor had it that one VC was seen floating on the surface.

April 2, 1966, we board LSTs at 1015 hours with much anticipation and anxiety. The trip to the beach was about 20 minutes. We are jam-packed. I have visions of D Day, bombs, planes, smoke, and carnage! There is a scraping sound and down goes the ramp. And to our surprise, courtesy of Major Jim Peterson, there was the 25th Infantry Division Band on the beach playing Stars and Stripes Forever and the Star Spangled Banner. Welcome to Vietnam.

April 2, 1966, we board LSTs at 1015 hours with much anticipation and anxiety. The trip to the beach was about 20 minutes. We are jam-packed. I have visions of D Day, bombs, planes, smoke, and carnage! There is a scraping sound and down goes the ramp. And to our surprise, courtesy of Major Jim Peterson, there was the 25th Infantry Division Band on the beach playing Stars and Stripes Forever and the Star Spangled Banner. Welcome to Vietnam.

The Downstairs View of the Trip

No complaining as the troopers were sardined in the hold, sleeping in hammocks. I took two trips down there. It is dark, crowded, smells of sweat and vomit—think steerage class. I talk to the Military Police wearing my editor’s hat and they report good behavior with maybe too many guys sick. There were approximately 1,800 soldiers and 1,000 marines down there.