Angel's Wing: A Shitty Mission - 25-26 Jan 1969

by Jerell E. "Jerry" Jarvis also see Angel's Wing Battle

The Aerorifles of D Troop (Air), 3/4 Cav (Centaurs) went to the aid of a RF/PF unit in a village near the Cambodian Border. They became surrounded by enemy troops. B Troop, 3/4 Cav was sent to rescue them. They too needed help and C Company, 4th Battalion, 9th Infantry (Manchus) was flown in by the 116th Assault Helicopter Company (Hornets). Two 105 Howitzers and crews were also brought in by Chinook from Fire Support Base Hamilton. It was a fierce battle that night. Jerry Jarvis, a grateful Centaur with the trapped Aerorifle Platoon, tells us what happened to them.

Part of this story is covered in the 10 March 1969 issue of the Tropic Lightning News.

.....................................................................................................................................................................................

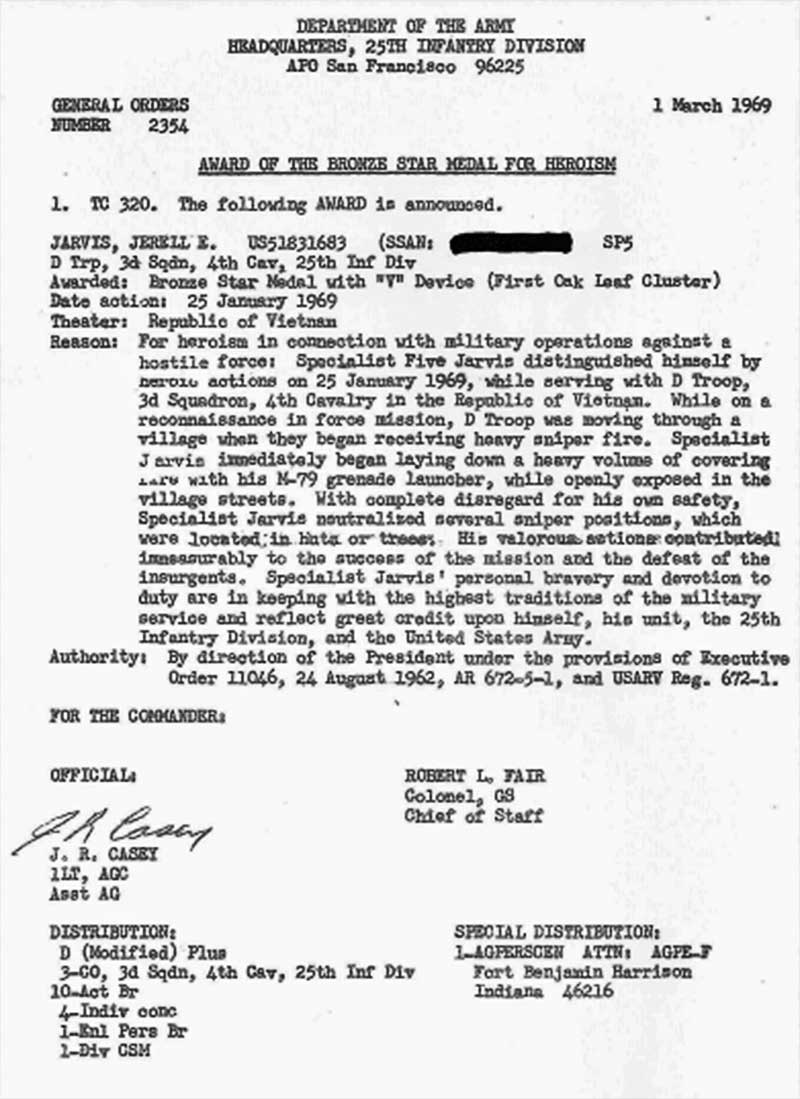

Webmaster note: Jerry was awarded the Bronze Star with V for his heroic actions as the man with the M79

On the morning of January 25, 1969, as I sat in my hootch, I contemplated what unit I should attach myself to next. I felt a little tired, because I had worked in the photo lab nearly all night, developing film from three days and nights with a track outfit outside base camp. The weather was pleasant, with the sun shining as it can only in South Viet Nam.

As a Public Information Office (PIO) photographer and writer, I more or less had a free hand when it came to deciding which unit within the ¾ Cav or the 25th Infantry Division I wanted to photograph and write stories about.

For some reason, I felt restless. Getting some badly needed sleep was just not on the menu for me. Maybe I was tired because my nervous system was still in overdrive from being with the mechanized unit. As I looked out the screen door of the hooch, some of the men from our Aero-Rifle platoon were casually walking out toward the flight line, wearing full field gear. Since they were not running full tilt, I knew they weren’t reacting to a call for help from a downed ship or reinforcing a Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol (LRRP) team in trouble. They were probably going on a planned mission.

I grabbed my camera, weapons, and field gear, then headed to the flight line, planning to join up with them. I asked one of the guys what the mission was. He replied, “We’re going to do a quick sweep of some village called Phuoc Luu, up near the Cambodian border, then return to base camp and remain on the usual stand-by status.”

His casual response gave me the impression that this would be a perfunctory mission, which was just perfect for taking field photos and maybe writing a human-interest story on the villagers interacting with GIs. I knew that the Tropic Lightning publication loved to print stories of this type, because it was good press for the folks back home to read—unlike the many blood & guts stories I had written previously that never made it past the screening of the “powers that be” and into the paper.

We loaded up on three or four “D” models and took off toward our destination. I recall that one of the other men had also mentioned that this particular village was in an area called “the Angels Wing.” I believe the name was derived from the Wing shaped section of the border between Cambodia and Viet Nam as it showed on the maps.

We loaded up on three or four “D” models and took off toward our destination. I recall that one of the other men had also mentioned that this particular village was in an area called “the Angels Wing.” I believe the name was derived from the Wing shaped section of the border between Cambodia and Viet Nam as it showed on the maps.

I could see a small village out of the chopper’s right door, and that endless expanse of elephant grass–covered terrain out the left door. On the other side of the village stretched a seemingly infinite number of flooded rice paddies, with not a single road in sight. What disturbed me was the multitude of footpaths freshly trampled in the elephant grass, to our west, and they all seemed to be converging on the village. Now . . . I wasn’t a trained infantryman, but I had flown over enough terrain to know that these trampled paths were a pretty good indication that a whole lot of enemy activity was going on around here. Literally hundreds of them led as far as the eye could see in every direction toward the border. To say I had an uneasy feeling in my gut was an understatement.

There seemed to be no discernible roads leading to the village, as far as I could see out the right door of the ship. The village was just sort of sitting in the middle of nowhere . . . no way in . . . and no way out. The rice paddies were flooded to the tops of the dikes, and it was obvious that no heavy armored vehicles could traverse this soggy, soft terrain. The short of it was: there was no chance that the proverbial “cavalry” (no pun intended) could come riding over the hill to pull our collective butts out of the fire, if necessary. This gave me an even stronger gut-level ill feeling that things might go bad for us when we went to make a sweep of this village.

We had a flight of two gunships accompanying us. One was a Heavy Scout, and the other was a HOG. One LOH accompanied us on the flight in. The LOH would be our advance recon as we moved into and through the village, while the gunships would cover us if we needed them. It was reassuring to see all of this backup air cover, because they could give us a lot of additional firepower if we got into a jam while sweeping the village. And since there were only about twenty of us going in, we definitely needed all the extra firepower backup we could get. In the months when I was pounding the ground as a PIO, I had seen more than one S-3 intelligence screw-up, where things got out of hand real quick for some leg outfit.

As we reached the village edge, the Slicks did a tight right-hand circle and came in for a steep landing, despite the ample open area around the landing zone (LZ). We disembarked in a couple of seconds, and the Slicks almost jumped out of the LZ in their takeoff, grabbing as much altitude as they could while banking out over the grasslands to the left.

This struck me as odd, because my experience as a crew chief had taught me that in a wide-open area such as this, Slicks usually take a shallower rate of climb-out from cold LZs. Steep climb-outs were usually reserved for hot LZs and/or small LZs surrounded by tall tree lines. I couldn’t help but think, “Do they know something we don’t know?”

The LZ was a large area about the size of a football field, with the village on one side and the grasslands on the other. There were no rice paddies or foliage between us and the first line of hootches at the village edge, just a big grassy expanse. We quickly formed up and proceeded toward the village edge, which was about 100 to 200 meters from our LZ. When we were about 20 to 30 meters from the first row of hootches, all hell broke loose from our two o’clock flank and our direct front. We were still pretty much out in the open at this time.

We immediately took up defensive positions in the prone position or behind any cover we could find. Believe me, there wasn’t much to choose from. The volume of incoming AK-47 fire was very heavy. After a couple of minutes, there seemed to be no specific direction that the fire was coming from. It seemed as if every hootch ahead of us was the source of the AK firing. Rounds were popping past us and over our heads with unnerving frequency.

We were pinned down pretty bad. There was no real cover close at hand, and nothing but elephant grasslands to our rear. In other words, we were caught in an exposed position with no viable route of retreat to better cover. The platoon leader (LT) yelled that the C&C had instructed us to make/fight our way into the village’s center, where there was an old French Fort. I think he also yelled that there was a unit of Ruff-Puffs (Rural Forces/Popular Forces) held up inside the fort as well.

Somehow, our platoon had become divided into two elements: four or five of us were on the right side of a narrow road leading into the village center, and the rest of the platoon was on the left side. We advanced in a leapfrog movement, trying to take advantage of any cover we could find. Those of us on the right side of the road half crawled and half crouched-ran from one skimpy bit of cover to the next. Rounds were popping past our heads and impacting the dirt around us. I think Charley was on three sides of us at this point. At the same time, both segments of the platoon came to paths that intersected in a crossroads about 100 meters into the village. Then things got even worse for us, as the enemy fire got much heavier.

We were under enemy fire from ground, tree, and hootch positions all around us. I’m pretty sure we were also taking some hostile fire from the rear. We were now surrounded on all sides.

Note: For some reason, I don’t recall that the LOH was still with us. Perhaps due to all of the other goings on around us, I just failed to notice the LOH buzzing overhead.

One of the men on our side (the right side) of the road shouted and motioned (while in a prone position) toward a tall tree a short distance to our front, roughly at the 11:00 position. The tree branches were moving, but there was no breeze or wind blowing. Just then, we all saw a rifle muzzle pop out from the tree branch foliage and fire a short burst of auto fire directly at our position. The rounds hit the road approximately ten feet from us. Those of us still in the crouching position dove for any cover we could find and tried to look invisible. It was clear that we were definitely in a bad place at the wrong time.

I spotted a pool of water across the road from my position, with a berm around it about two feet high. This was the only place I could see, from my vantage point, that offered us any sort of cover from the enemy tree and hootch firing positions surrounding us. All I could think was, “G-d, thank you—thank you!”

I jumped up and made a mad dash for the pool. I literally dove in head first, trying to get low enough that the incoming AK rounds wouldn’t hit me. The other three or four men with me also jumped up, ran like hell for the pool, and dove in. The water was only about three feet deep, but if we squatted down low enough, we could just get our heads below the top of the surrounding dirt berm. The tree positions and the multiple hootches to our front opened up on us even more intensely. The rounds were splashing in the water all around us, as well as impacting on the inside of the berm on the opposite side of the pool.

We all submerged ourselves until our chins were barely above the water line. The water was a dark brown color and had a G-d awful stench to it. It suddenly dawned on me that we were taking cover in the village cesspool, because the smell was so horrendous, and little brown lumps bobbed in the water all around us. Judging from its reek, it was a well-used one. The bottom was real soft and gooey. We’ve all heard the term “being in deep shit.” Well, we literally were deep in human shit and piss up to our chins.

We could see the rest of the platoon trying to cross the intersection about 30 to 50 meters to our left, but they kept getting driven back by a withering volume of enemy fire. Peeking just over the top of the berm, I was huddled against, I saw several other enemy tree positions firing down on all of us. Things didn’t look good for the rest of the platoon . . . or for us, either.

One of the men crawled out of the cesspool and did a low crawl towards the path we had just crossed, and than went into a kneeling position in the middle of the path that ran alongside the cesspool. From this exposed position, he could get a clear view and shot at the various enemy firing positions . . . free from the interfering foliage around us.

He had an M-79 grenade launcher with two claymore bags full of ammunition, along with an M-16 slung from his right shoulder and a few bandoleers of clips around his left shoulder. I could see the cesspool water draining out of his claymore bags. He opened fire on the first tree position with the M-79 grenade launcher, then started pivoting on his knee and firing multiple rounds in every direction as fast as he could reload the chunker.

AK rounds were impacting on the road around him. Each time a round hit, a small plume of dust and dirt was kicked up. At least one spray of these dust plums and debris flew into his face and eyes, causing him to hit the prone position for a couple of seconds. He then got back up and proceeded to fire and reload as rapidly as he could. The first M-79 round that he fired hit the tree position dead-on. We saw an AK fall out of the tree and a leg dangling down from the foliage, not moving. He then pivoted and started to fire rounds over the cesspool at the trees to our right front. Several M-79 rounds later, the firing from those trees stopped.

The NVA in those trees were either dead or had the hell scared out of them . . . or else they were laughing so hard at the sight of American GIs chin deep in piss and shit that they couldn’t aim their rifles straight. Either way, there was no more fire coming at us from them. He then started to fire round after round at some thatched-wall hootches to our front-right and left-forward flanks. Several of the rounds went in through the windows and exploded inside the hootches or hit just below the window openings. Here again, the firing stopped from those particular positions.

There were AK rounds still impacting all around him on the road, as well as in the bushes just behind him. He emptied one of the claymore bags of M-79 rounds and switched to taking round after round out of the bag hanging from his left shoulder. He was left-handed, so he was shooting from his left shoulder. Taking rounds out of the bag on his left side slowed him down a bit. At some point, there were no more M-79 rounds left in the bag, and the guy dropped flat to the ground in the middle of the road. There were still rounds impacting all around him. He then did the fastest low crawl in recorded history toward the cesspool and dove head-first over the berm back into the water.

Interesting observation:

Now think about this scene for a moment. . . . The first time he dove into that cesspool, he had no idea what it was, just that it offered badly needed cover. The second time . . . he knew exactly what it was . . . and he was still highly motivated enough by the sound of AK rounds popping past his head and hitting the dirt around him to dive in it again for cover. Isn’t it amazing how AK rounds popping around you can lower your inhibitions and otherwise motivate you?

By this time, the incoming AK fire had slowed down a bit, and this allowed the rest of the platoon to get past the crossroads to our left and into somewhat better firing and cover positions. The guys crouching in the cesspool also got a little breather (no pun intended) from the incoming rounds. Raising their heads above the berm, they started shooting in every direction, because there still seemed to be movement and hostile fire coming from all around them. The cesspool gang and the crossroads group moved forward and converged on the road leading into the fort, and we all joined up as one unit again. I remember that as I crawled over the surrounding berm, the tip of my M-16’s barrel dunked into the water and made a hissing sound . . . it was that hot!

The platoon did a leapfrog movement toward where the C&C had told us the French Fort was. We had moved probably another 200 meters down the road before we laid eyes on the so-called French Fort. My heart sank when I saw it. We were expecting to see a real fort, with multi strands of concertina wire and claymores set up all around it. What lay ahead was a rather tall triangular-shaped berm about 40 meters on a side, with one scanty string of barbed wire and no claymores at all. An entryway appeared to be on the left side of the part facing us. A row of hootches lined one side of the road, with the fort on the other. Probably not more than 30 meters of road separated them.

Just as the platoon got within view of the fort, renewed volleys of AK automatic fire broke out again from our right and left sides. A fair amount of firing came at us from our rear flank as well. I had been in intense firefights before, but never had I experienced the volume of incoming rounds that I did that afternoon. The constant sound of rounds “cracking” past us and over our heads was unbelievable. Everyone in the platoon was firing as fast as he could and then swapping out the empty clips for full ones. It seemed that each of us was returning fire toward a different direction. We were, in fact, surrounded on three sides with the fort in front of us.

I was down to one clip of M-16 ammo with a partial clip in my rifle, when the LT yelled, “Everyone into the fort!” We all made a mad crouching dash across the exposed road to the fort entrance. I believe I was one of the last men through the opening, as I was probably the farthest away from the entrance when the LT shouted the order. The first thing I saw as I came stumbling through the entrance was a group of eight to ten ragtag-looking Ruff Puffs squatting down inside the opening. They were armed with WW II weapons: M-1 Garands, Carbines, and one rusty-barreled BAR. I instantly realized that our hope of getting resupplied with ammo was now moot, because their vintage weapons weren’t compatible with ours.

At this point the rest of our platoon had moved farther into the fort, and had taken cover behind the berm facing the hootches across the road. The enemy fire had pretty much died back down at this point. The LT was talking on the radio and then did a low duck walk at the base of the wall toward me. He stopped to talk to each of the other men as he went down the line. As it turned out, not a single man had been hit in the withering enemy fire. To this day, I don’t know how this was possible.

When he got to me, the first words out of his mouth were: “Are you okay?” I responded with an affirmative shake of my head, as I was too out of breath to utter a verbal response. The second thing he said was: “How much ammo do you have?” I held up my one remaining full M-16 clip and pointed to the three frags hanging from my webbing. “This is it,” I said. “I’m completely out of M-79 rounds, too!” His response was a resounding “Shit!!!” The third thing he said was: “What in the hell is that smell? You smell like shit!” “It’s a long story,” I replied. “I’ll tell you about it someday.” At the moment, I wasn’t in much of a mood to explain anything.

One of the RF/PFs spoke somewhat broken English. He told us that he and the others in his small unit had been trapped in the fort for the past several days, and that they were pretty much out of ammunition and water, with no food at all. Well, I guess that S3 had it wrong, because they had sent approximately twenty men into a hot situation, when they should’ve sent in a couple of companies. He also related that the enemy forces surrounding us were NVA and not VC, and the NVAs had just crossed over the border into the village during the previous two nights.

As I sat there listening to the RF/PF guy, I recall wondering how only a few of them with nearly no ammo and food were able to hold off the NVA’s numerically superior forces. I couldn’t help but think that maybe we were sharing space with the local detachment of VC. And that they might turn on us and finish us off from inside the fort. As I look back, it still doesn’t make any sense to me. I mean, that fort was such a poor fighting position that a determined platoon of Girl Scouts armed with slingshots could’ve overrun it.

The LT was on the radio, talking to the C&C. He informed the old man that we were in a real bad situation and just about out of ammunition and were taking fire anytime we stuck our heads above the upper edge of the fort’s walls. I seriously doubt that he passed on this information about our ammo situation in such a way that Charley would have understood its content, because we always assumed that Charley was listening in on our radio frequencies. Had Charley known about our lack of ammo plight, they would’ve overrun us in a heartbeat. But for some reason, they didn’t.

During this time, we were also taking hits from satchel charges being propelled over the fort’s walls by small explosive charges. We could see and hear that the charge launching point was just on the other side of the hootches across the road from us. First, we would hear the sound of the small propelling charge, then we’d see a cloth satchel come sailing through the air into the fort’s courtyard. They all hit near the center of the compound, where there was no one close by. The explosions were pretty big, but there was no shrapnel being shot out. So, if a satchel charge didn’t actually hit one of us, we were okay. For the life of me, I can’t figure out why Charley didn’t just drop a few mortar rounds in on us, because we had no real cover inside the fort, except for the doorway where the RF/PFs were cowering. Just a few well-placed mortar rounds would’ve torn us apart from the flying shrapnel. However, these explosive charges played havoc on our nerves, and we flinched every time we heard the propelling charge go off.

While all of this was going on, the LT was on the radio with the C&C overhead. The LT relayed to us that the old man said we had to stay put, because there was no possibility of an armor outfit or reinforcements getting to us right away. The terrain surrounding the village was flooded, and the track vehicles would sink in the flooded rice paddies. He then said that an LOH would try to make a treetop run over the fort and drop boxes of ammo to us.

About five minutes later, we heard the familiar sound of an LOH heading toward our position at high speed just above the treetops. Just as he sped over our position, a huge volume of AK fire broke loose from everywhere around the outside of the fort. I don’t know how many AKs opened up on the LOH, but there were a lot of them. I also heard the lower-pitched thump-thump sound of one or two 51 cals opening up on him once he got a short distance beyond us. The LOH flew away at full speed, just barely clearing the treetops on the opposite side of the fort. Unfortunately, because of the intense enemy firing, he wasn’t able to drop any ammo boxes into the fort, or, if he did drop them, they didn’t land inside the fort.

A few minutes later, we were informed by the C&C that there would not be another attempt to resupply us with ammo, as the LOH pilot had radioed that several 51 Cals had fired at him on his first run, and it would be suicidal for him to make another attempt, now that the enemy knew what we were up to.

Up until this point in time, we had no idea of the actual size of the enemy element surrounding us, but we did know that they were NVA regulars (thanks to our RF/PF roommates), but that was it. After hearing the muzzle reports from one or two 51s and then the LOH pilot report of possibly even more 51s located around us, we were pretty sure that the enemy element was on the order of a brigade size or even larger.

NOTE: I recall reading somewhere that 51 Cals were usually assigned to brigade-sized or larger elements of the NVA. The fact that there were multiple 51s deployed around us suggests to me that the enemy element was a hell of a lot more than just a couple of heavy weapons platoons.

It’s my best guess that among all of us trapped within that fort, we had fewer than 200 rounds of M-16 of ammunition and perhaps only 10 to 20 frags remaining. I don’t recall seeing anyone with a belt of M-60 ammo still draped around his neck, so we probably had little or no M-60 ammo remaining either. The bottom line was that even a squad of enemy soldiers could’ve just walked right over us.

By this time, it was getting on toward nightfall, and we talked among ourselves about what would go down next and when it would happen. We pretty much all agreed that once night set in, Charley would attack and overrun us. As the guys talked, I had the feeling that we all knew we would never see the morning’s dawn. This was further driven home to me when the guy next to me asked how much ammo I had left. I told him, “One full magazine and a partial in my M-16.” He then said, “I’m completely out. Give me one of your rounds!” I ejected the partial magazine from my weapon and handed it to him. He peeled off one round and then inserted the clip with the remaining rounds into his weapon. I remember just sitting there, thinking to myself; “Why did he slip that round out of the clip?” Then it dawned on me, “Oh, I get it!” I followed suit and peeled off one round from my full clip, before loading it into my weapon. That round went into my breast pocket.

As the sun dropped behind the horizon, and the evening twilight took over, the only sound coming from outside the fort was the occasional thumping of satchel charges being launched into the fort and the explosions when they landed. At about this time, the LT got a call from the C&C overhead. The LT passed on to us the order that we were to keep our heads down below the top edge of the fort’s berms. (Like he really had to tell us to do this!) No reason was given for this order.

The night grew pitch black, as it can only in Viet Nam. It seemed as if one minute it was dusk and then someone turned off the lights, immersing us in total darkness. There was no moon that night or maybe there were heavy clouds overhead, I don’t recall which. But I couldn’t see the opposite side of the fort (30 feet away?) from my position alongside the LT. I remember thinking, “Great!!! First, no ammo, and now we can’t even tell when they come over the top after us.”

Once it got pitch black around us, everything became eerily quiet. Charley had stopped thumping the satchel charges into the fort and not a single shot was being fired anywhere in the village. Sometimes, everything being quiet is more scary than when the shooting is going on! I know that may sound crazy, but your imaginative expectations of what may be coming can sometimes scare you more than the reality of the moment. It was the kind of quiet that can set your nerves and imagination into hyper-drive. The kind of total quiet that makes you just know that all hell is about to break loose, and that you’re going to be on the losing side of that hell storm.

I couldn’t help but wonder how it would be to die while living my worst nightmare of having an empty gun in my hand . . . and not even be able to go down with a fight. Being out of ammo in the middle of a firefight or an ambush gone wrong had been the reoccurring theme of my many nightmares while I was back at base camp. It was a feeling of helplessness escorted by foreboding doom.

I kept checking my survival knife. It sort of gave me a sense of false security, even though I knew it was a losing proposition to take a knife to a gunfight—but it was all that I might shortly have left to fight with. I used to spend a lot of time sharpening and honing the blade. It was actually sharp enough to shave with. In all of those hours I’d spent sharpening that blade, had I ever imagined that at some point, it might actually be the only weapon I’d have to go up against an AK-armed enemy soldier?

A bit later, the flare ships started dropping parachute flares at what looked to be two or three klicks North of the village. The distant flare cast a golden glow over our position. As they sank in the distance, the shadows within the fort grew longer and longer, then another flare would light up and the shadows would jump to being short again. The moving shadows almost had a surreal effect all around us. I recall thinking, “Great. Now Charley has the way lit for him. Aren’t we in a bad enough situation already?” Let’s face it, rational thinking is not exactly the hallmark of fear and a foreboding of what will inevitably come.

From the fall of darkness until about midnight, everything was eerily quiet around us. All of us remained totally silent as we strained our hearing for the first sign that we were going to be attacked. It’s one thing to be full of adrenaline in the middle of a firefight—at those times, you don’t have time to contemplate your own end. Adrenaline will do that to you. But crouching behind a ten-meter-high embankment of dirt with plenty of time to contemplate what might come next is a whole other thing. I have to admit that I was scared. And I’m willing to bet that so were the men around me.

I kept thinking about my wife back in the world. We had been married a couple of weeks before I was drafted. (Note: I joined the Army on what was known as the “buddy plan” . . . me and the two MPs it took to drag me down to the induction station.) One might say that I had a definite U.S. prefix (draftee) attitude when it came to being in the army. And now here I was reliving the battle of the Little Big Horn—Asian style. G-d really has a warped sense of humor sometimes.

I had avoided mentioning to my wife, in my letters home, that I was a crew chief on a HOG gunship, or that I was now going into the field as a PIO writer/photographer two or three times a week with different field units. As far as she knew, I was working in a hangar back in Cu Chi base camp, repairing helicopters and drinking beer at night while watching gung-ho John Wayne movies. I couldn’t help but wonder how she would take the news, or if even my remains would get back to the world for her to bury. I know that this might be coming across as a bit melodramatic sounding,….but this was what I was thinking at the time.

A few hours after darkness fell, we could hear the sound of chopper rotors in the distance to the South of us, and then passing to our right front and than a horrendous volume of AK fire following a few seconds later with hundreds of tracer rounds flying up into the night sky. The firing seemed to be coming from a good distance beyond the hootches nearest to us, near to where we had inserted that previous afternoon. Then we heard the lower pitched and slower thumping sound of the 51 Cals going off as well. I’m not sure how many 51s were shooting, but I’m certain that there was more than just one. I have to believe that the guys flying in those choppers were either shitting their drawers or were constipated for the next several days from overworking their sphincter muscles. If my memory is correct, the flare ships had stopped dropping flairs just prior to the revival of the choppers.

I could tell that the chopper blade noise was not coming from Hueys, as I was very familiar with what they sounded like. The only conclusion I could come to was that they were twin-rotored Chinooks. I recall that at least half a dozen ships passed by us. I could hear them coming in on their final approach, then hover for a few brief seconds, then fly off. All I could think was, “Those guys have the balls of a brass monkey … to knowingly fly in and then actually hover while the entire NVA Army was trying to blow them away.” This went on for a couple of minutes, then everything just went silent. No AKs firing or anything.

A short while later, a horrendous firefight erupted in the same area where we had heard the Chinooks hovering. There were hundreds of red tracer paths going one way and green tracers going the opposite direction, and something that sounded an awful lot like the main guns on tanks firing every couple of seconds. This confused us, in as we had been told that armored units couldn’t get to us. Yet,….. I could clearly distinguish the main tank guns firing away, along with a hell of a lot of M-60, M-16, and AK fire (I don’t recall there being any 51 Cal fire at this point in time).

I didn’t know a Chinook could lift a tank! But it sure sounded like a main tank gun. I also noticed the sound of raindrops falling around us within the fort—but there was no rain actual falling on us! I began to wonder whether all of this wasn’t some sort of twisted nightmare, and that I was actually back at base camp and would wake up with a start, totally soaked in sweat, as had happened many times in the past. This firefight kept up for better than an hour, before everything suddenly went dead silent. An occasional shot was fired, but compared to what had gone on earlier, it was nothing. The deathly quiet resumed. Again, we felt pretty much alone and once again were contemplating what our near-term future would be with only a dirt berm separating us from Charley.

It was two to three hours before sunrise, and the cold air hung heavy with the smell of cordite and dampness (I can still smell it today, nearly fifty years later). I kept hoping against hope that we would see a beautiful column of armored personnel carriers and tanks come rumbling down the road towards the fort . . . but they just didn’t materialize. All that we had was this deathly silence surrounding us, not knowing when Charley would decide to overrun us. All of this time, our radio had remained silent—not a single word from our C&C. We were not given a clue about what was going on across the village from us, or why Chinooks were flying all over the place.

Just before dawn, we received a radio message from C&C that one (or two?) companies of infantry would be coming in to extract us from the fort—and that we were not to open fire on them as they approached the fort. I think I heard the LT sarcastically mutter something to the effect that we don’t have anything to fire at them with.

Just before the sun peeked over the horizon, two columns of infantrymen came down the road, shrouded in morning mist. They were walking on either side of the road. The heavy morning mist gave them an almost ethereal appearance. They had to be the most beautiful sight I’d ever seen, even if they weren’t the tanks and armored personnel carriers we had hoped and prayed for. For the first time since the previous afternoon, I was able to envision that there would be a tomorrow for us. When they got up to the fort, someone yelled from outside the fort for us to move out and join up with them. Needless to say, we did just that in record time.

As soon as I encountered the first man, I remember saying to him, “Can you give me a couple clips of ammo?” He gave me a strange look, then tossed me a bandoleer of magazines, and asked; “You guys were out of ammo?” I responded with something to the effect: “No—I still have one full clip”! I then motioned back toward the RF/PFs behind me and said, “Compared to them, we were in good shape.”

He didn’t say anything else and just shook his head, while gazing over my shoulder. I followed his gaze and turned around to see what it was he was looking at, was dumbfounded to see that there were no RF/PFs. They had just disappeared into thin air.

We proceeded to join up with the infantry rescue element and walked out of the village. It was about 500 meters from the fort entrance to the edge of the village. Our platoon had intermingled with the infantry unit as we walked out. By this time, I was hyper-vigilant and kept scanning the hootches to our right for some sign of movement—but there wasn’t any. I noticed that my hands were trembling just a bit, and my legs felt a little rubbery as we walked. I guess that after having no sleep for two days and many hours of vacillating between overdoses of adrenaline, depression, and just being plain scared, it made perfect sense that I would be like this.

As we approached the edge of the village, I saw a large clearing with the village on one side and the grasslands on the other. It was the same LZ that we had inserted to the previous afternoon.. As we proceeded into the clearing, I was struck by the most bizarre sight I’d ever seen. There were enemy bodies sprawled in every direction. Some were in contorted, twisted positions, and others just lay there as if they were only asleep. Walking past one of the bodies, I remember looking down into the man’s face as he lay on his back. The eyelids were wide open, and I could see the ground directly under his head through his empty eye sockets. Whatever had hit him had removed the top of his head from the hairline back.

A little farther on, we passed a lonely leafless tree trunk standing towards the edge of the clearing, with an NVA in a khaki uniform standing up against it. He was dead and pinned to the tree in some manner. It was macabre, to say the least. I could see that there were many, many little dark pock marks on his exposed skin. I turned to the guy to my right and asked, “What the hell happened?” He replied, “The shit-hooks [his words] had inserted baby Howitzers along with us, and Charley made the dumb mistake of charging head-on into them while they were rapidly firing flechette and beehive rounds from fully depressed muzzles.”

Just then it dawned on me why there had been the sound of raindrops falling inside the fort . . . they were flechettes or G-d only knows what else coming over the wall into the fort from those big guns. Now I understood how all of the pieces fit together. There wasn’t any armor being brought in by the Chinooks. It was infantry and Howitzers. In other words, the tanks couldn’t make it in, so they sent in the big guns instead.

As we walked past their old firing positions from the previous night, I could see what seemed like thousands of shell casings all over the ground. I asked one of the men how much ammo they had fired that night? He replied, “I have no idea. All I know is that our squad emptied several ammo cans of M-16 ammo, and we had shot off a lot of M-60 ammo as well.” That anecdotal comment is the last memory I have from this mission. I don’t recall how or when the Aero-rifle platoon and I got back to base camp. My memory is a total blank on this point.

The fog of battle is an encompassing effect that all soldiers experience, when the bullets are flying and their adrenaline flow is high. Each person sees the fight from a different vantage point on the battlefield and remembers only so many things. I suspect that if I were able to find some of the guys who were on that mission with me and compare notes, we each would have a slightly different story to tell . . . each being accurate . . . but different.

To this day, I don’t know how it was possible that we all came through this mission in one piece. I suspect that truly the “Angels” were looking down on us and brought us all home.

In retrospect, I’ve come to the conclusion that one possible logical reason we survived, was that the NVA unit(s) and its commander were in their first very first action after crossing over the boarder from Cambodia. I mean, why would “experienced” soldiers take-up sniper positions high up in trees, where they would surely be neutralized in a hurry? Why would an experienced commander have hesitated to overrun a smaller force (such as ours) within that old fort? Why did he elect to take on an enemy (our reinforcements) across an open field with zero cover, as apposed from the direction of the hootches bordering that open area? Why did our C&C not have the covering gun ships saturate the village outside of the fort with rockets and/or mini-gun and/or door gun M-60 suppressive fire, as our position was well defined and more or less protected from being collaterally damaged? I’ve pondered these (and many other questions) over and over in my mind these past forty years.

After action report:

The day after returning to base camp, our hootch maid (Mia) found two long sticks, and used them to pick up my cesspool-smelling fatigues and boots off the floor, carried them outside, wrinkling her nose all the while gagging. She then dropped them into a half 55 gallon drum (the same ones used to burn shit) and covered them with JP-4 or diesel fuel. They laid in that tub soaking for two days before she fished them out again and proceeded to wash them several times over. My boots were included in this process. I gave her a big tip the following payday (smile).

Be well my brothers.

Jerry Jarvis

Also see Angel's Wing Battle