Keep'Em Flying - 1969

.....................................................................................................................................................................................

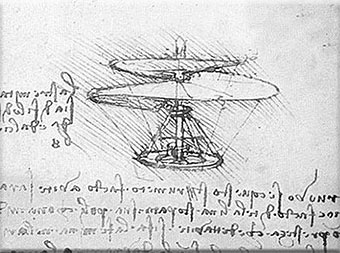

Some History of Helicopters: - Leonardo Da Vinci, an Italian inventor conceived the first idea of an “air screw” back in the late 1400’s. But, it would be centuries later, following the flights of hot air balloons, following the flights of gliders, and after the flights of motorized fix wings before a successful “rotor wing flight” would take place. The flight would be by a French inventor, Ventor Bequet who would attain an altitude of 15’ and fly a distance of 64’. That flight would take place in Aug./Sept. of 1907. During the next couple of decades, several other Frenchmen, such as Paul Cornu and Etienne Oehmichen would make improvements and advances of rotor wing flight. This new thought and technology would continue slowly, but steadily over the next several decades before the helicopter would come in reliable reality. The real successful helicopter flights were made by the Germans in 1936, and the first rotor wing in the United States was the Sikorsky Model VS-300, designed by Russian born, Igor Sikorsky in the late 1930’s. After that in the 1940’s and 1950’s, the United States continued rotor wing development at an accelerated pace and the US Army found good use for the helicopter for observation, communication and rescue.

Some History of Helicopters: - Leonardo Da Vinci, an Italian inventor conceived the first idea of an “air screw” back in the late 1400’s. But, it would be centuries later, following the flights of hot air balloons, following the flights of gliders, and after the flights of motorized fix wings before a successful “rotor wing flight” would take place. The flight would be by a French inventor, Ventor Bequet who would attain an altitude of 15’ and fly a distance of 64’. That flight would take place in Aug./Sept. of 1907. During the next couple of decades, several other Frenchmen, such as Paul Cornu and Etienne Oehmichen would make improvements and advances of rotor wing flight. This new thought and technology would continue slowly, but steadily over the next several decades before the helicopter would come in reliable reality. The real successful helicopter flights were made by the Germans in 1936, and the first rotor wing in the United States was the Sikorsky Model VS-300, designed by Russian born, Igor Sikorsky in the late 1930’s. After that in the 1940’s and 1950’s, the United States continued rotor wing development at an accelerated pace and the US Army found good use for the helicopter for observation, communication and rescue.

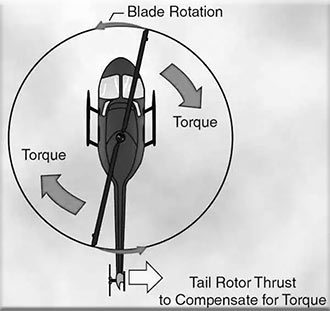

Real Technical Problems. – No doubt the Wright brothers and other inventors of fixed wing flight faced many new challenges in learning about flight. And, no doubt control problems would be one of them. The combustion engine was a great help in giving the aircraft the power it needed to give flight, but a great secondary problem with the helicopter was the reverse torque caused by the powered rotating wing. This torque caused the fuselage of the helicopter want to spin in the opposite direction of the powered rotating wing.

Real Technical Problems. – No doubt the Wright brothers and other inventors of fixed wing flight faced many new challenges in learning about flight. And, no doubt control problems would be one of them. The combustion engine was a great help in giving the aircraft the power it needed to give flight, but a great secondary problem with the helicopter was the reverse torque caused by the powered rotating wing. This torque caused the fuselage of the helicopter want to spin in the opposite direction of the powered rotating wing.

Some of My History With 3/4 Cavalry - A year or so ago I was challenged by our web master to write an article about helicopter maintenance with “D” Troop, 3/4 Cavalry. Although, at this time it has been 50 years ago, there still remains some prominent memories of those days in Vietnam that took place while serving as a crewmember, a maintenance mechanic on “slicks” (MOS 67N20) and added later was the (MOS 67Y20) on the Cobra Gunship. I did also assist as a mechanic with the “loach” (Hughes OH-6A) from time to time.

It was in the fall of 1965 when I first saw the “Huey” up close for the first time. I was a senior in high school heading home on board of the school bus. As we were leaving the Stockton, Missouri high school, we noticed many soldiers in town and we asked our bus driver, “Hey, what’s going on?” He told us that an Air Force fighter jet had crashed somewhere around Fair Play, Missouri and these men were a part of the search/recovery team. The bus route I rode on took about one and a half hours to get me home. When I was getting home, and just stepping off the bus, I heard the “thump, thump” of helicopter blades, and a Huey chopper appeared over the treed area of our farm and flew directly overhead of our house. The cargo doors were open and I waved at the crew members, and they acknowledged. “Wow,” I thought, “That would be a neat job to do if I was in the military.” I didn’t have any idea that in just a short few years later I would be so involved with such an aircraft. My dad was coming up from the barn because it was time to feed our livestock and milk the cows, and I asked him what he knew of this incident. He told me that earlier he was out in our corn field picking corn, and there had been a couple of jets go overhead and the one was only about tree top high. I changed into my “work” clothes and headed to the barn to get the milking done, turning on an AM radio as soon as I entered the barn. The radio was broadcasting news of the crash. The crash site had originally been broadcasted as Fair Play, Missouri, about 15 miles south/east across country from our place. But, dad had said that these jets were headed north/west when he saw them, and that was the same direction the helicopter I observed was flying. In the process of milking the cows, the small dirt road skirting the boundary of our farm got active with various military vehicles. About the time the milking was done, they announced over the radio that the AF jet had crashed at Arnica, Missouri, about 3 miles North/West of our home. After the chores were done, some neighbor boys and I began to explore. Almost everywhere we went, Air Force Security stopped us, and made us turn around. We found out that the place of impact was on the north forty acres of Otis Vickers, a good friend of ours. That night after dark, the neighbor boys and I traveled the three mile trek by foot and got up to the crash site. Although there was AF Security all around, we got within feet of the remains of the crash, even at times could almost touch some of the soldiers of that security force. The plane had crashed through a wooded area of large hardwood trees, and about the largest piece of plane that looked by any means intact was the engine.

As I grew up, mechanics seemed to be a niche for me. At age 12, I had watched and helped a man overhaul a truck engine for a Ford truck my dad had. Later in my teen years, I rebuilt/repaired some car engines. And farm boys, having very little cash, always had to innovate in keeping equipment running. Sometimes bailing wire had more use than just being used in bundling hay.

For Basic Training, I was sent to Ft. Leonard Wood, Missouri. Out of basic training I was promoted to a Private E-2. I had no leave time after basic, but was sent to my AIT assignment at Ft. Eustis, Virginia. The orders said I was going to Helicopter Maintenance School. “WOW!!” I was a happy soldier. I was given the opportunity to become a squad leader in our class, and also was made the assistant class commander. An unfortunate incident of our class commander being busted promoted me to class commander. I did well in the helicopter maintenance school and out of school was promoted to Specialist Four. Then, for some crazy reason, at graduation, I got orders for Ft. Campbell, Kentucky while most of my class was sent home on leave and their next assignment would be Vietnam. At Ft. Campbell, I would be “volunteered” for classes in a ranger school designed to train a soldier in extensive map reading, intelligence gathering, etc.

I arrived in Vietnam late April of ’69, and was assigned to the 25th Infantry Division, ¾ Cavalry at Cu Chi. It was quite a change. Hot, muggy, insects, and it seemed like Artillery was always being fired. SP5 Jim Rodgers was on CQ for “D” Troop and picked me up. He asked me where I was from, so I said, “Kansas City, Missouri.” He then exclaimed he was from Lone Jack, Missouri, and was really happy to find someone who had come from an area so close to his home. He didn’t seem to remember my name, so he went about introducing me as “The Kansas City Kid.” That title got shortened fairly quickly as, “KC,” a name I am know by my fellow troopers until this day.

When I got in maintenance, the Service Platoon officer was CPT Dixon. My direct platoon Sergeant was an E-7, Bill Moore. My direct squad leader was a red headed trooper by the name E-5 SGT Bill Wilson. If I recall correctly, there was another group of maintenance men who were under the leadership of SGT Bill Gregory. If I recall correctly SGT Gregory’s men worked on a night shift – and later, Wilson’s crew took that shift of work for a period of time. It may have been that these crews swapped back and forth of night crew and day crew?? Another trooper that came in about the same time that I did was another SP4 by the name of Carroll Evanstead, who later took over the night crew of SGT Gregory, and I would take over the Service Platoon of SGT Wilson during the days.

Can It Fly? - The bumble bee given his physique, should not be able to fly, or so I have been told. Its body mass in compared to the bee’s wing structure, according to people who study bugs, says it should not fly? But that insect, not having a scientific mind does not know the better and still flies very well. The same thought also exists in the minds of some in regard to the helicopter. The concept of a rotating wing that would provide lift and forward motion (and other things) was quite a challenging concept. But, after a half century of trial and error, testing and failure, the helicopter became a true reality for military and civilian use. It would become like a hovering Humming Bird that could take flight in any direction from that hover. It would take special skilled men that would continue to maintain and fly these precision aircraft.

Can It Fly? - The bumble bee given his physique, should not be able to fly, or so I have been told. Its body mass in compared to the bee’s wing structure, according to people who study bugs, says it should not fly? But that insect, not having a scientific mind does not know the better and still flies very well. The same thought also exists in the minds of some in regard to the helicopter. The concept of a rotating wing that would provide lift and forward motion (and other things) was quite a challenging concept. But, after a half century of trial and error, testing and failure, the helicopter became a true reality for military and civilian use. It would become like a hovering Humming Bird that could take flight in any direction from that hover. It would take special skilled men that would continue to maintain and fly these precision aircraft.

The Makeup of the Aircraft – The study and application of gyrostatics (the branch of physics that investigates laws governing the rotation of solid bodies) would be challenged with this “gyroplane” that we flew in our Cavalry unit. Even with all the calculations that engineers of flight were making, it remained that different materials needed to construct the aircraft needed vast improvements. Weight of materials, stress of the materials in the rotating wing would be even different than in fixed wing aircraft. The helicopter has stresses and material fatigue all the time. The helicopter in the very nature of just running is vibrating and straining every component. The rotating wing is wanting to go one way, and the rest of the body is wanting to do something else. Even the helicopter when not at “work,” the components of its structure are being stressed. Then when we add “work” to the rotating wing, it adds more stresses. Added to those stresses in work, are those who operate the aircraft. Even though tests are made to find minimums and maximum strengths, these tests do not remove any of the stresses the aircraft endures. There were many times our aircraft were asked by our operators (pilots and crew) to perform greater than the suggested arena of “work” by the manufacturer.

Every nut, bolt, rivet, bearing, wing, gear, mount, etc. had its “life.” For example, a bolt used on the tail rotor assembly had to be changed out after a certain length of time, even though it looked perfectly good to the eye. This was usually done during 100 hour PE Inspections. Torque methods were used, and in most uses, these bolts and nuts were safety wired. Safety slippages marks were utilized on bolt and nut heads and other components to assure that everything was held and holding in place. Every day the crew chief and pilots checked their aircraft. Every 25 flying hours, our crew chiefs took oil samples and did various other checks to his aircraft. Every 100 flying hours, the aircraft was brought in for a Periodical Inspection (PE) where components were closely inspected, and if/because the “Life” of the component had been met, were changed out.

If a Crew Chief, or maintenance service worker found a bolt needing replacement, one would not just grab any similar bolt as its replacement. Nope, the motor pool was not the place to go. We had aircraft supply that had a FSN (Federal Stock Number) for every component on the aircraft. These parts had endured the testing for the “life” expected and only these parts were to be used.

The Levels of Aircraft Maintenance – If I recall correctly, there were about four levels of maintenance to the helicopter. Each level of maintenance had its limits of what we were allowed to do. The basic daily maintenance was performed by the Crew Chief. One might think this was just one time a day, but keep in mind that in flying combat sorties, sometimes simple repairs were needed in between flights. Next was the level of maintenance that I worked into at the hanger. We performed tasks of maintenance usually under the 100 hr PE inspections, but often we assisted Crew Chiefs with their checks and repairs. Beyond our hanger maintenance was our support of 725th Maintenance and they specialized in doing more complicated things than we did in our hanger. However, there were times when our maintenance personnel would be assisted by the 725 mechanics coming to our hanger, or us going to their hanger to help them. The next level of maintenance was way down the runway from us and I do not recall the name of that team. But, usually when we had to go that far up to have work done on our helicopter, our aircraft usually met it “DEROS” time and it would be phased out and a replacement aircraft would brought in.

Personnel – I served with the greatest of maintenance men. Other maintenance NCO’s may make the same claim, but I claim that I had the “chiefs” of them all. I am not going to mention names for fear that I will miss naming some. With the exception of a very few, all of the mechanics had the desire to fly. In the beginning, I flew countless missions that was in substitution to gunners and crew chiefs who desired to have a “day off.” Of course this was usually under the approval of my maintenance leaders, and flight operations. Yes, there were times while flying that incidents happened that made me wish I had stayed in the hanger turning wrenches. As I became crew leader and platoon leader, I had to learn how to guide these men. There were some who worked great together and some who did not. I had to learn how to team up these so that conflict would not exist. Then, as an NCO, I was a buffer between my men and the upper chain of command. I know there were many times I had to learn to “sort” out the information to keep everything calm. I pulled no punches, there were some leaders above me that were “breathing air that someone else really deserved to breath.”

I learned over time that some guys were better working on certain parts of the aircraft than on other areas. I usually had a least two mechanics working together. Not only were they company for each other, but they could watch and aid one another work. I found most of my personnel to be self- starters, assertive and most took pride in their work. If anything can be said about the troopers who worked in maintenance, I believe they were men who have often been overlooked as “unsung heroes.” Keeping our helicopters in good flying order demanded long hours of work, basically no time off and repeated constant attention to similar old problems and always the development of new problems that these men in all levels would need to overcome.

There were also demands of the maintenance personnel for company details outside of working in the hanger. Guard duty on the bunker line, KP, and Ash and Trash were some of those details.

Most, if not all of the permanent assigned flying personnel were exempt from these duties. Those that were E-5 and above missed being detailed to KP, etc., but even those of us who were E-5 had a duty rotate to us for bunker line guard, especially those of us who had “outside the wire” experience. As an E-5, I was told to “polish up” and “dress your best” and go on “guard mount inspection.” Out of that inspection, some would stay back at “somewhere” and not have to go on the “sweep patrols” outside the wire and also be on the bunker line all night long. I learned early on that the chances of being picked for that “somewhere” duty would not be given to anyone who had faced regular “combat” duty of any sorts. In other words, a non-combat position of a “clerk” was not going to be exposed to sweep patrols, listening posts or bunker line duty.

Some Experiences in Helicopter Maintenance & Learning Tricks Of The Trade

,,,The Kink

As a mechanic, trained as a 67N20 for the “Slicks,” my first job assignment in the hanger was to work on a Cobra. SGT Wade H. Moore, the maintenance platoon leader gave me the task of putting new hydraulic lines on the transmission. He told me to be sure and make sure there were no kinks and the line was firmly clamped so that no excess shaking or chaffing would take place. Then, he pointed out where the line was to go and told me that another line for the other side would be coming in later. I don’t know how many times I tried fitting that line, looking at the TM manual, and trying it again to fit, and every time I came up with a kink. I dreaded exposing my ignorance, but I went to him and told him my troubles. So, accompanying him, I showed him the problem, and we decided that the line was about 1 ½ inches to long. I then was instructed to go over to 725 Maintenance to have them make up a new line, which they promptly did and it installed perfectly. That afternoon, the second line came in and I went to install it. It turned out to be 1 ½ inches too short. So, a lesson learned. With maintenance, one must look beyond what may seem to be obvious. As mentioned before, the aircraft is designed for proper fitting components, yet some hookups are so near alike that simple applications could be made. Later on, when I came leader of the service platoon, I used my “experience” of that occasion to men that worked under me

...Maintenance In The Boonies

Maintenance did not always stay in the hanger or in the Cu Chi base camp. Our helicopters may leave Cu Chi and go to various fire bases or other base camps to be assessable for quicker response. One day some officers from flight operations and maintenance came to the hanger and approached another maintenance worker and myself. We had a Cobra flown by a Warrant, Mr. Bobo, make a forced landing because of a 42 degree gear box failure on the drive line of the tail rotor. They wanted us to volunteer to go out in the “boonies” and make repair. So, quickly SP4 Richard Waite and I, with our hearts in our throats, and parts and wrenches, were flown to an area near the base of Nui Ba Den. Although we had security forces in the area, being exposed was not our cup of tea. We did the repair. Later on I became a part of a team that I will call Rescue/Recovery of downed aircraft, and was involved with “out in the boonies” activities.

...Cobra Tail Rotor issue

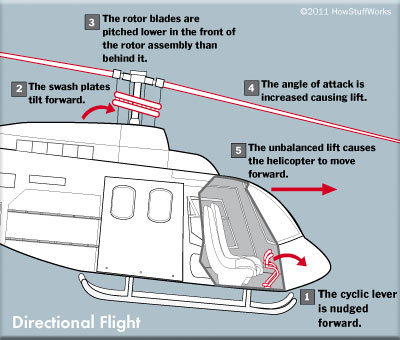

Something that always seemed to be a reasonable complaint of the pilots of the Cobra was the in-ability for the gunship to turn out of a gun run in a certain direction. I don’t mean “in-ability in that it would not make the turn, but because of the gyro-torque, the aircraft turned better one way than it did the other. What we did in maintenance was to change the “timing” position of the tail rotor sprocket chain on the sprocket a few degrees. In changing the sprocket chain setting, it would cause the pedals to be a little offset to the pilot in the neutral or normal flying position, but in the need for extra pitch effect to accomplish the “pull-out turn”, the tail rotor would have added pitch to make that turn more responsive. It seems to me that the adjustment caused the right pedal about one inch lower than the left pedal under normal hover position?

... Cobra Fuel Linear Actuator

Another thing that was taught to me by a Bell Helicopter Tech was an adjustment that could be made to the Linear Actuator on the Fuel Control. There were two designs put on Cobra engines. One design of which I will call the “two screw” calibration, could be adjusted in such a way that under need of extra power, the pilot could “beep” in added movement of the Actuator to give, (so to speak) added fuel to the engine. The pilot, of course had to cautioned to use this ability in the case of “breaking right” or “breaking left” at the conclusion of a gun run, and once at normal flight, “beep down” this control so that the aircraft would not fly with its wings in an over speed condition. Only some pilots requested this, and the word got around of what I could do, and a few different times I had Cobra pilots from other units fly in and ask me to make that adjustment on their aircraft. Sometimes I could make these adjustment, but I was limited because of the design of which Linear Actuator that was installed on the particular Cobra.

...Cobra Vertical Fin

The Cobra had a vertical like wing in its design to promote a sideways lift-like pull to help in its higher speed guidance and turns. The “skin” that covered that wing like surface was tightly riveted to a very smooth contour to give it that sideways lift. On one occasion that I remember, we were moving a maintenance stand around to do work on the tail rotor section and we bumped that part of the Vertical Fin with the stand, and it “popped” and a nice hole/rip broke open. I don’t know if in combat use the metal had temper-hardened, making it brittle, but in any case, the “skin” had to be repaired/replaced.

...Cobra Emergency Hytraulics

The Cobra also had something called a “Hydraulic Accumulator” in its system of hydraulics. This accumulator was designed to have enough pressurized hydraulic fluid within itself to allow the aircraft to have hydraulic assist to the controls in case of hydraulics failure. Without hydraulic assist on the cyclic and collective controls, the feedback of vibrating, jerking power coming from the rotor wings will leave the flight pilots with a lot of control problems. Each pulse of feedback power is felt, and really “shake” you up.

...Cobra’s Super Shaft

One thing that often happened with the Cobra was the failure of the grease seal on the Super Shaft. The super shaft was the “drive shaft” between the engine and transmission. Often pilots would need to use a “cyclic climb” when coming out of a gun run and that action would contribute to this grease seal failure because in that maneuver the super shaft would no longer be straight from one point to the other, (engine to transmission) but these two aircraft parts would flex out of alignment. The transmission was and did flex on its mounts as the aircraft pulled out of these maneuvers. Thus the “O” Ring seal would allow the grease to escape. Crew chiefs and maintenance alike hated to see the mess the grease would make as it was “flung” out, plus pilots sometimes got a grinding sound and vibrating sensation. Repairs had to be attended to immediately. In maintenance, we called that work, “repacking the super shaft.”

...Auto-Rotation

Auto-Rotation, the ability to fly/glide without power to somewhat a controlled landing was a fantastic feature with our aircraft. So many others and I would not be alive today without that feature. I have no idea how many pilots ever practiced shooting auto-rotations or even having to do one, but every aircraft we had coming out of maintenance had their rotating blades adjusted so that in case of power train failure, this feature could be used. Every aircraft following their 100 hr. inspection underwent test flight. Even if the head blade assembly and/or blades had not been removed from the mast, and even if the controlling arms and pitch guide tubes had not been loosened in any way, the aircraft would still go through an “auto-rotation” test. There was a minimum and a maximum RPM of the blades that the rotating wings had to retain while flying/gliding without power. If the maximum pitch was too much, over speed of the blades would happen and if the minimum was too low, there would be no glide ability. Always when we changed out the blades, we tried to not change the length/settings of the push/pull tubes. However sometimes when the head grip assembly and blades were changed out, the needed settings would be changed and certainly needed to be “tested” and adjusted. I will say this, there can be quite a scare when in test flying a chopper fresh out of maintenance, and auto-rotation RPM is so minimum that the blades would quickly stall if you couldn’t reapply power. Been there and done that. You just hope the engine won’t quit until you get back in to make adjustments. (it never did happen to me to have engine failure on test flights.) But, if the RPM is not right, turning a few flats on the push/pull tube turnbuckle could have the chopper back with safe auto-rotation abilities. Most mechanics would go over the instructions found in the Tech Manuals and most it memorized. However, maintenance had to keep adjusting and test flying until it was the correct RPM. One thing our Company SOP required is that when flying an auto rotation, you never would let the aircraft touch the ground. We would normally fly up to an altitude of a couple thousand feet and auto-rotate down to about 300 feet, start the process of powering up and fly back up in altitude. Many times there would be troopers/soldiers of non-combat job who wanted to fly with us on test flights so they could take pictures and in most cases get the feel of what it was like to fly in a helicopter. This we allowed if it looked like the test flight would be routine, and often we would tell them that if they got “sick” on the flight, they would have to help wash and wax the aircraft. All would agree, and certainly one of the things that had to be done was wash and wax the chopper after it came out of maintenance. Sometimes it took as many as three spiraling auto rotations to make them sick, but the crew chiefs loved their help in cleaning up his ship following maintenance.

...Blade Tracking see Blade Tracking Discussion

Another problem we always faced was the tracking of blades. Blades not tracking with each other caused bad vibrations during flight. It was a constant need to keep vibrations at a minimum for the sake of more comfort for flight personnel, as well for the health of the “life” of aircraft parts. Blades had a “life” span, and had to changed out, but I do not recall very many choppers which used up the “life” of a rotor blade. The “slicks” were very exposed to combat damage, and often blades would be changed out before the hundred hour PE inspection needed to be performed. Some of the most frustrating work would go into the changing out of blades and the following tracking process. Sometimes “out of the shipping container, brand new” blades just wouldn’t match in their circular fling about the helicopter mast. Trim tabs on the end of the trailing edge would be adjusted, as well as the push/pull tubes had to be adjusted. Another thing that had to be done from time to time was the putting lead weights in the blade grip pins to equalize the unbalanced condition. I can recall one incident where CW3 Tom Shirley and a couple of us were up all night trying to get a helicopter with newly installed blades to track and balance right. Time after time we adjusted and flew and kept having a bad one to one vibration. Finally, about midnight, we pulled both blades off and put new ones on. We were able to track again, make adjustment on the trim tabs, test fly and come back in as a very dense fog was rolling in. If I recall correctly, we made one more balance adjustment, but could not make another flight because of the fog and got to bed about 0400, and at 0700 Mr. Shirley and I went out in the dense fog, and cranked up that slick. We ran it up to an “out of ground affect” altitude, and with the fog swirling around, we could not see to set it down for fear of hitting another aircraft. Mr. Shirley called up “Tower” and they would not give permission for takeoff because of the dense fog. We could not see to set down. “Tower” had informed us that clear skies were above 2000 feet, so we proceeded with a takeoff to that altitude to bright sunshine. I did hear one remark from the “Man in the Tower” say, “Who’s that flying by my tower?” I don’t think we replied and by good fortune, the chopper was flying very well. After a while in the air, the sun started burning off the fog, we landed back at the “Corral” and we signed the chopper over to Operations for use.

...Our Limits Of Maintenance

We were limited as to how “deep” into the aircraft mechanics our level maintenance would go. Most work consisted of the “Crew Chief” level consisted of the “daily” inspections. The crew chief also did some given hours of taking oil sampling inspections. The maintenance crews would also give support to some of the work the crew chief would need to perform, especially if there had been battle damage. Also helping the Crew Chief would be his assigned gunner. The gunner really helped with the weapons although the crew chief helped in that work also. Maintenance also helped with weapons as well. During the one hundred hour PE’s maintenance crews routinely removed certain parts, such as filters of both oil and fuel, inspected for such things as metal chips or other damage. Bearings, mounts, control linkage, all things related to the requested needs of the aircraft were repaired or replaced.

Complaints

...A couple of things to complain about! Helicopter maintenance tried to keep up with the technology of this quickly developing aircraft, but one thing that seemed to lag behind was the best tools that could be used. Sometimes it seemed we would be using tools that some farmer might have used on his horse drawn mowing machine. Duck Bill Pliers and Dikes used in safety wiring different items on the aircraft could disappear from tool boxes in a flash. When I went on

R & R to Hawaii in November of 1969, I went to a Sears store and personally purchased four sets of these pliers and brought them back with me. Most of them got borrowed and disappeared.

...Another complaint has to do with the “PM Bulletins” that came out in regard to helicopter maintenance. I guess these must have been printed and issued back in the days of the A-B models of the huey, and someone decided to send them to us to review and comply. But, we had the D-H model Hueys, and the information was out of date. One thing mentioned in the particular PM Bulletin was the fact that we needed to lubricate the Mixing Lever bearings on the cyclic stick. The older model A-B and maybe C models did not use sealed bearings in the mixing levers, so maybe they needed to be lubricated?? But our D and H models had sealed bearings. About the same time that this “bulletin” came to us, we also got a new maintenance supervisor, who was not a trained mechanic. He just had rank. So, He told me to lubricate these ‘sealed’ bearings. I argued with him, stating that “One cannot break that seal without causing future problems with the bearings caused by infiltration of foreign matter, and thus having a bearing problem.” Sure enough, we did one, and it wasn’t too long before the pilots complained that the Cyclic Stick was binding and grabbing. We wound up changing out the whole cyclic stick, and that is not an easy job. (Oh, and that “ranking individual…. Well, he didn’t last long in that position!”)

Oh, these are just some memories about the Mechanical Maintenance on the choppers. I could come up with a bunch more. Then too, there are also the Avionics and Armor sections who had their problems as well. I am proud that I flew on the helicopters as well working on then to “Keep’em Flying.” And, I am glad I had a reputation from our pilots as a person who could be turned to for solving maintenance problems. “KC” Allen B. Allcock